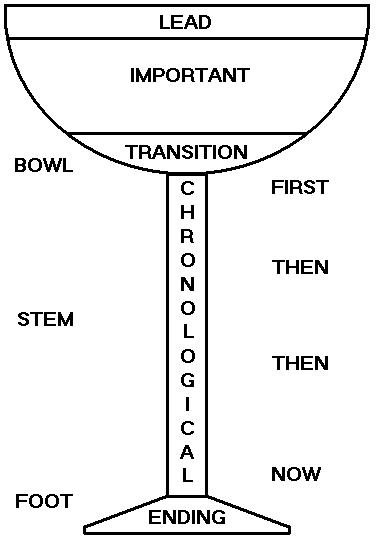

We can explain some things better by treating them twice, once descriptively and then chronologically. The “champagne glass” form has the traditional beginning, telling the readers what the story’s about and why it’s important, and the traditional ending giving a sense of closure.

The middle has two sections divided by a clear transition. The first section treats the subject descriptively and analytically, and then transitions to a second section retelling the story in narrative chronological form. This form works best to straighten out a complex series of events, such as a long budget process, perfecting an invention, controversial election results, or a complicated rescue.

Here’s my favorite, from the St. Petersburg Times. (By the way, a manatee is a marine mammal resembling a walrus, about ten feet long and weighing 1000 pounds as an adult. It must surface to breathe at least every 20 minutes.)

FIREFIGHTERS RESCUE MANATEE FROM CRAB TRAP ROPE

SAFETY HARBOR – Struggling to free itself from a crab trap rope wrapped around its neck and body, a young manatee was rescued by two city firefighters.

The men worked nearly an hour to calm the 10-foot-long mammal before freeing it Thursday.

“With anything that big and powerful, you could get hurt if you got in its way,” said Safety Harbor Fire Capt. Max Shimer, who estimated the animal’s weight at 600 pounds. Shimer and firefighter-paramedic Ray Duke freed the manatee.

“We knew they are gentle creatures and wouldn’t hurt us on purpose. But we didn’t know if this one was injured or how it would react to us. We just played it by ear,” Shimer said.

The rescue operation began shortly after 8 a.m. when the struggling manatee was spotted by Bill Pleso, the city building maintenance foreman. He was making his daily inspection of the municipal pier when he saw the animal about 150 yards north of the pier.

“I could see he was tangled in a crab trap,” Pleso said later. “He was dragging two buoys with him.”

Pleso, who said he regularly sees manatees around the pier, radioed City Hall for help. The Florida Marine Patrol was called, as were the Florida Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission and Sea World. The two agencies and Sea World are involved in the state’s mammal rescue and rehabilitation program.

Fire Chief Jay Stout said his men agreed to attempt the rescue when he learned it would be several hours before the Sea World team would arrive. Since no one knew if the mammal was injured, Stout said he felt the rush was necessary.

Shimer and Duke got into a boat and paddled up to the manatee. “It was frightened at first, but gradually it seemed to sense we weren’t going to hurt it,” said Shimer. It did not appear injured.

For nearly an hour, the men reached out to calm the manatee each time it surfaced to breathe. Finally, Duke reached into the water, held the rope as close to the animal’s neck as he could and cut through the rope with a pocket knife.When the rope fell away and the manatee was free, “about five other manatees, all much larger, suddenly appeared out of nowhere,” Shimer said. “They came up to the surface and rubbed faces and noses. It was a pretty neat experience.”

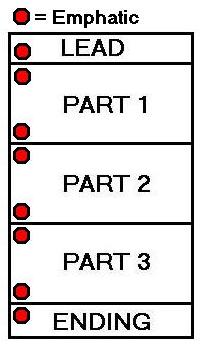

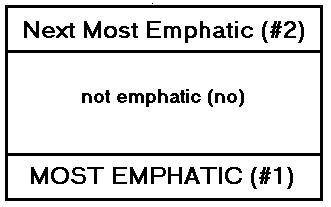

The lead tells us what the story is about: “a young manatee was rescued by two city firefighters,” followed by details of the creature’s plight and the rescue. Halfway through, the story gets retold in chronological order: “The rescue operation began shortly after 8 a.m….”

And the story ends with Shimer’s terrific quote. In traditional inverted-pyramid thinking, that quote is too good to come at the end; an editor might move it up, weakening its power in the most emphatic position, the end.

Champagne glass pieces are inherently long, and they’re hard to cut. You would choose this form because the second, chronological telling helps the reader understand complex events.

[Had any adventures with this form? Let’s hear them.]